Imagine you worked for months to craft a new policy and when you finally announce it, your staff applauds. Why are they so thrilled? Because they not only knew it was coming but also had a chance to shape its direction. Even those who were iffy about it nod with understanding when you explain why you made the decision.

If this sounds too good to be true, it doesn’t have to be! That is the power of fair process, a concept developed by W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne that we adapted as a decision-making approach for managers and leaders.

In a nutshell, the purpose of fair process is to create space for authentic, equitable, and inclusive engagement and build clarity about decisions, resulting in stronger relationships, smoother implementation, and better overall outcomes. Practicing fair process means being clear about who the decision-maker is, inviting input from those who will be impacted (and being explicit about how it will be used), explaining the decision, and outlining expectations once a decision has been made. While it is especially helpful for bigger or trickier decisions, the elements of fair process provide helpful guideposts for all decisions no matter their size or scope.

Before you initiate fair process, answer some key questions:

☐ What is the main question, problem, or decision you’re wrestling with?

☐ What parts of the decision do you need input on? How will the input be used to inform the decision?

☐ Who is the decision-maker(s)? If the decision-maker(s) is not the same person driving or owning the process, how will the decision-maker(s) and process owner coordinate?

☐ What is the timeline for the decision? At what points will input be gathered?

☐ What criteria (values, guiding principles) will be used to decide?

Tips & Tools for Executing the 3 E’s of Fair Process (plus a bonus!)

Fair process has three mutually reinforcing elements: engagement, explanation, and expectation clarity. For decisions that are especially high-stakes or are recurring, you might also add a bonus E: evaluation.

Most of the advice in this article is geared towards processes where the decision-maker is also the person driving the process. If that’s not the case, keep in mind the following:

- The process owner and the decision-maker(s) should communicate regularly, including:

- At the outset, to define success, share parameters, align on decision-making criteria, and outline the process for gathering input and communicating the decision.

- Throughout the engagement process, to stay abreast of input gathered.

- After the decision has been made and communicated, to debrief and learn from the process.

- As much as possible, the decision-maker should make time to hear and engage with input directly.

- Depending on the context, the decision-maker (rather than the process owner) may want to be the person to communicate the final decision and clarify expectations moving forward.

1. Engagement

Would you plan a dinner party without having any clue what your guests like to eat? Even if you already have some menu items in mind, we assume you’d at least ask about dietary restrictions. If you’d check in before a simple dinner party, you’d of course want to check in about decisions that have an impact on people’s lives and livelihood. (Not to understate the importance of asking for dietary restrictions—after all, some allergies are life-threatening!) While most decisions we make as managers are not a matter of life or death, they’re usually far from inconsequential.

Fair process always starts with engagement, which can mean the difference between whether our team members feel considered, valued, and respected—especially when it comes to decisions that impact them. For engagement to be meaningful, it needs to be empathetic and transparent—people need to feel like their opinions were considered and that their perspective matters.

Unfortunately, getting input on decisions can be like cleaning your fridge. You know it’s something you should do, but you avoid it because it’s time- and energy-intensive, or you’re not sure where to begin, or you’re afraid of what you’ll find. Below are some tips that break down the process.

Be honest about your starting point.

It’s rare to start a decision-making process with a blank slate—usually, there are at least a few parameters or preferences. Yet we often see people entering the “engagement” phase without transparency about what’s negotiable and what’s not. Transparency builds trust and ensures that you make the best use of everyone’s time. No one likes to spend energy sharing input that won’t make a difference.

Your starting point includes:

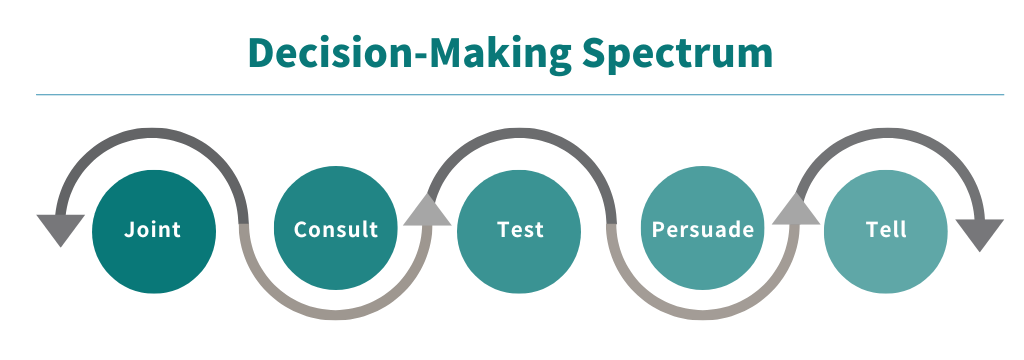

- Your decision-making mode. Your decision-making mode will influence what questions you ask. It’s also a useful way to convey to people how much influence they can have on the final decision. Generally speaking, the closer you are to “tell” mode, the more you will want to focus on surfacing risks and mitigations for implementation. The closer you are to “joint” decision-making, the more your questions should be geared towards brainstorming and problem-solving.

- What’s really up for discussion (and what’s not). What parts do you need input on, and what’s already decided (and why)? For example, you might say, “I’m working to plan our first team retreat for next year. I’m already certain that it’ll have to be virtual because it’s the only way we can have full participation. What I’d appreciate input on is how we can structure it so that it’s fun and engaging.”

- Your biases. Don’t feign neutrality if you have an opinion. And, even if you don’t have a strongly held opinion, you have biases that, left unchecked, will influence how you approach decision-making. If the decision were left entirely to you, what would you do?

Identify the right stakeholders.

Think about what experience, expertise, or perspective each stakeholder brings to the decision and when each person should be involved.

Consider those who:

- Will be most impacted (especially negatively impacted) by the decision

- Have experience and expertise with the problem you’re trying to solve

- Will likely anticipate risks and problems that you might miss

- Have desires or considerations that might be in the minority or be different from yours

- Have personal identities, experiences, or roles that may be on the margins of your team

- Have been historically left out of similar decision-making processes

Get dissent early.

One common pitfall we see is leaders approaching fair process as a way to build consensus. This approach focuses on sharing talking points or asking leading questions to generate agreement rather than surfacing points of tension. But remember that the purpose of fair process isn’t to make everyone happy or to arrive at a consensus—it’s to create space for authentic, equitable, and inclusive engagement and build clarity about decisions. Engagement helps leaders gather input to inform their decision-making. When you don’t invite honesty, you won’t get the information that you need when it’ll be most helpful.

Assume that disagreement will surface at some point—whether or not it’s invited. It’s up to you to design the process so that you can get it early (when you can make choices or collaborate to mitigate concerns), rather than waiting for them to come up later when you’ll have to defend your decision against those concerns.

The most effective way to get dissent early is to acknowledge differences upfront. For example, you could say, “Given our diversity of experiences, I don’t expect everyone to have the same questions or concerns. In fact, we’ll be better off if I hear where you have a different opinion.” You can also name the parts that you think will be most contentious and ask about those directly.

Whatever your mode, include questions that invite pushback and concerns. This is especially important if you’re operating in a low-trust environment, if you’re still building relationships with stakeholders, if your stakeholders are on the margins of your team, or if conflict avoidance is a feature of your organizational culture.

Sample questions:

- What’s one thing you could imagine going wrong with how we’re approaching this?

- One option we’re considering is A—what parts of that plan do you have concerns about? How would you talk me out of this decision?

- What’s an outcome you absolutely want to avoid?

- What’s an unpopular opinion you have about this?

Try this tool: Encourage stakeholders to offer ideas and engage them in identifying benefits, drawbacks, and alternatives with our pros, cons, and mitigations tool. This tool is especially useful when you’re in joint, consult, or test mode.

Keep people in the loop.

For particularly tricky or big decision-making processes, engagement isn’t just about the time that you spend gathering input (whether via survey, 1-1s, or group conversations)—it’s also about the time and efforts that you put into keeping people informed along the way. (For sample emails, check out our Fair Process Examples resource.)

2. Explanation

Once you make a decision, explain how you got there.

When you share your decision, include the following:

- Re-state the context for the decision (see the “before you begin” section above)

- Recap the decision-making process (we talked to X people over Y timeframe)

- Share the criteria, values, or guiding principles used to make the decision

- Acknowledge and thank the people who shared input

- Share anticipated drawbacks, risks, or negative impacts and how you plan to mitigate or avoid them

- (If relevant) Share when you might revisit the decision

The more important or far-reaching a decision, the more ways you need to communicate about it. Think through all the opportunities you have (or should create) to share the decision, build awareness, and increase adoption—from all-staff meetings, to internal email announcements, to 1-1s, to Ask Me Anything sessions.

Check out our Fair Process Examples for some sample email announcements.

3. Expectation clarity

A critical part of generating buy-in and smoothing implementation is setting and aligning on expectations for moving forward. Many important organizational or team-wide decisions will have implications not just for how people do things (new practices, systems, or policies), but what success looks like. Make the implicit explicit and lay out what will be different.

Update roles and goals as necessary.

Revisit your role expectations and goals and make sure they reflect any changes to expectations that will be part of how your staff will be evaluated.

Be honest about what you don’t know.

Clarity doesn’t have to mean certainty. If there’s anything you feel unclear about or that is still uncertain, share it. If you feel uncertain, those further from the decision-making process likely feel even more so. If you’re not transparent about what you don’t know, you risk people assuming that you’re intentionally keeping information from them.

Bonus: Evaluation

It might not always be practical or helpful to do a step-back after every decision. However, the bigger the decision or the more likely it will recur (e.g., in goal-setting or budgeting), the more important it is for the decision-maker and/or process owner to reflect on it. Evaluate the outcome of your decision and the process you used to get there. Identify lessons learned to carry you into your next decision-making cycle.

Debrief.

If you were in joint decision-making mode, set aside time to do a group debrief. Or, consider setting up 1-1 or small group debriefs with key stakeholders to get feedback on what worked (or didn’t work) in your decision-making process.

Check for equity in the results.

Use whatever data is available to you to evaluate the outcomes of your decision. If data isn’t readily available, you might consider generating some by sending out a quick survey or having managers check in with their staff and report back. In reviewing it, you’ll be looking for evidence of negative unintended consequences, particularly for the most marginalized members of your team.

To see fair process in action, take a look at Fair Process Examples.