See also, Part 1: How to Receive Feedback (but trust us—it’s okay if you read these out of order!).

Imagine this: you’re the field director of a statewide LGBTQ organization and you’ve spent the last two months drafting and refining your team’s goals for the following year. You’ve consulted with your staff and executive director, and you feel like you’ve finally landed in a good place. Two days before your ED plans to bring the goals to the board for approval, a field organizer approaches you and says, “I’m not sure that the goals are achievable.” After you probe a bit, she shares that the goal you’ve set for turning out Latinx people (a community of which you’re not a part) at Lobby Days is tokenizing, and that goes against your organization’s mission and the intention of the work. This is your first time hearing this concern from anyone. In addition to feeling a little surprised, you’re not totally convinced.

What do you do?

Whether you’re a field director, chief of staff, or school principal—if you’ve ever received challenging feedback from someone you manage, this situation probably feels familiar.

Uncovering the iceberg

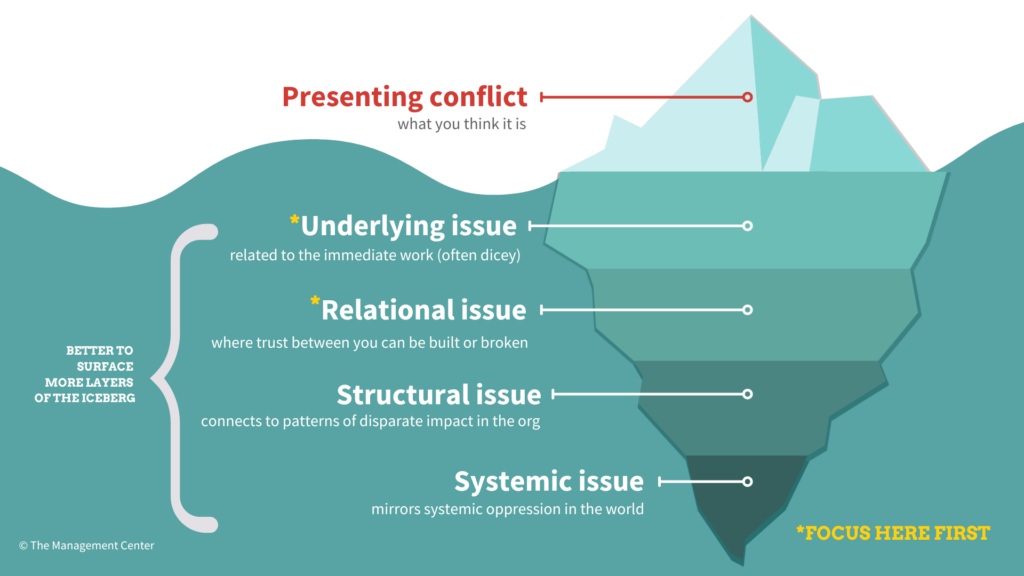

At TMC, this is what we’d call a dicey issue. Dicey feedback is often related to diversity, inclusion, equity, belonging, or culture. It’s usually a clue that there’s an “iceberg,” where the problem on the surface is attached to a larger, multi-layered, and complex issue.

Dicey feedback is not easy to hear, which is why it’s important to slow down and get in the mindset to engage with it. How you engage with the staff member who raised the concern and how you tackle the issue could have significant implications not just for your working relationship, but also your organization’s ability to advance equity and inclusion. Below, we present a framework to help you listen for the concern beneath the concern.

For the scenario described above, let’s take a look at the layers of the iceberg:

| Layer | What’s Happening |

|---|---|

| Presenting conflict | Field organizer doesn’t believe that the goals are achievable. |

| Underlying issue | She sees one of the goals as tokenizing to her community, which goes against the intention of the work. She’s also worried about risking her relationships with community members who might feel tokenized. |

| Relational | She’s hoping that you’ll trust her to engage with her on this. |

| Structural | In this organization, field organizers are the lowest paid, the least supported administratively, are rarely asked for input on big decisions, and experience the highest turnover. |

| Systemic | There’s a broad progressive movement pattern of BIPOC field organizers being the least likely to advance into leadership positions within campaigns. |

It can be tempting to focus on resolving the presenting conflict. But focusing on the presenting conflict without at least digging for underlying and relational issues puts you at great risk of missing what’s really going on. This can cause long-term damage to your relationship and your results. Even if there is no iceberg, digging for it won’t cause damage—if anything, it communicates that you’re open to feedback and multiple perspectives.

Below are some questions you can ask yourself (to reflect on what other factors might be at play) and them (to dig deeper and get under all the layers):

| Questions to ask yourself | Questions to ask them |

|---|---|

|

|

Listen, Engage, Learn

As managers relating to our staff, we’re more likely to give feedback than to receive it. It’s often not an expectation or norm for staff to give feedback to their managers and giving (critical) feedback is trickier and riskier when there’s positional power involved. On top of that, if the feedback is on a dicey issue, it can be especially stressful for your staff to share it, which means you may not get that feedback until it’s too late (if ever).

To make it easier for staff to share feedback and resolve issues sooner, demonstrate that you’re open and able to receive feedback, especially across lines of difference and power. Treat the ability to do so as a core competency for managers (and ideally for all staff when you are looking to build a strong feedback culture).

1. Listen effectively

To dig below the surface, resist the urge to defend your ideas, persuade the other person, or problem-solve. Take the time to understand what’s really going on by doing the following first:

1. Press pause. Slowing down helps us listen better. Get yourself into an open mindset by reminding yourself that there’s no need to judge, decide, solve, or refute. Assess how you’re feeling. Defensiveness, anger, and resentment are all valid feelings that can get in the way of listening. Take a breath and, before saying anything else, thank them for bringing it up.

2. Ask questions. Probe to see more of the iceberg, not to validate or test any assumptions that you might have. Try these questions:

- Is there more to this feedback?

- Is this connected to any patterns that you have noticed?

- Is there any context you think I might be missing?

- If we were to move on as planned, what do you think would be at stake? What do you think the impact would be?

3. Repeat-back (not refute-back!). Check that you’re fully understanding what’s going on for them, and give them a chance to correct any misunderstandings. Highlight any areas of agreement.

2. Engage in the feedback

Once you’re on the same page about the content of the input, engage with it as a problem to solve as a team. Note: This part doesn’t have to happen immediately after you’ve received the feedback. It is okay—and sometimes even better—to take some time to process and follow up after you’ve listened, asked questions, and done your repeat-back.

1. Tie together. Share what you’re thinking and feeling. This is your chance to bring your staff in as a collaborator, especially if you are facing pressures or have context that they might not know about. Then, tie together what’s true for both of you, understanding that your experiences do not have to be mutually exclusive.

Here’s some sample language you can use…

| …to transparently share. | …to tie together |

|---|---|

|

|

2. New paths are possible. Think of ways to move forward that go beyond either/or (100% your way or their way). Seek out a third (or fourth, or fifth…) path or, if you can’t take a new course, look for mitigations to address the issues that are being raised. For instance, you could say, “While I can’t change the grant proposal the board already approved, I agree that we need to adjust our deliverables. How about we look for ways to trim 25% of the demands that are disproportionately impacting our admin team.”

3. Learn with and through an equity and inclusion lens

You can’t solve an iceberg issue in a single conversation, but you can use that conversation to get better at spotting and addressing similar issues.

1. Examine how it went. Once decisions have been made, get meta: debrief the conversation itself to assess how you handled their input at your next check-in. In the debrief, you can simply ask for a plus/delta. Remember that this conversation is about learning from the interaction to make it easier for them to bring you feedback in the future; it’s not about debriefing the decision itself (though you may want to do that at another point).

2. Remember the iceberg! Let this interaction open your eyes to other potential issues as you move forward. More importantly, make space to check in on how things are going and seek opportunities to continue the conversation before issues arise (see the “Ask for it” section of Part 1).

Remember our scenario in which you’re the field director and your field organizer shares some tough feedback? To see how these steps would play out in the scenario, check out our case study on receiving feedback.